Introduction

EPISODE GUIDE

EPISODE 1

EPISODE 2

- MY LAST SUMMER AT THE FELLOWSHIP AND THE LOS ANGELES 60 YEARS OF LIVING ARCHITECTURE PAVILION

- THE ROSS COTTAGE AND A THESIS

- IN WRIGHT'S HAND

EPISODE 3

OTHER ESSAYS

- WHAT KIND OF A MAN WAS MR. WRIGHT TO WORK FOR?

- THE MERRY WIVES OF TALIESIN, A FEW HUSBANDS, PLUS SOME MERRY MEN

- A SUMMER'S WORK -- NOT IN THE TALIESIN DRAFTING ROOM: THE NEILS HOUSE

"IN THE CAUSE OF ARCHITECTURE":

COMMENTARIES IN MEMORIAM

PROLOGUE

I was born in 1921 at St. Luke's Hospital in Faribault, Minnesota, very much like every one else to one male and one female parent. They raised me, up to a point, but I have always felt that I was pretty much on my own after about four or five years of age, no fault of my parents. My intent here is to explore the roots of my architectural interest, and to get to where I am trying to go, I am going to frame this dialogue as:

AN ARCHITECTURAL BIOGRAPHY

IN THE BEGINNING

When I tried to get started on a Frank Lloyd Wright website, I kept coming back to my architectural roots, beginning in my preteen years. So I have decided not to give in to a nostalgic journey into youth, but rather to examine my exposure to quality architecture at an early age and the result of that exposure on how I think about architecture today. Frank Lloyd Wright is at the center of the experience but he is not the beginning. Beauty and integrity are part of the beginning and were the key words from day one, along with a sense of fairness, which was instilled in me by my mother at an early age. A sense of the beautiful came from I know not where. We were not an intellectual family but we did have the Book of Knowledge close at hand, and I always received musically or structurally related gifts at Christmas. One of my favorite toys was a set of multi-colored wood blocks starting with an inch-and-a-half cube, the next one an inch-and-a-half square and three inches long, and the larges one was one-and-one-half inches square and six inches long. My favorite exercise was to see how far I could cantilever the largest block and how much weight it took to retain that cantilever.

|

In the 1920's we did have electricity, indoor plumbing, central heat, and silent movies. The talking movies arrived with the Jazz Singer in 1927, and radio and the refrigerator made their debut in about 1930. We spent a lot of time out-of-doors devising our own entertainment. All meals were family affairs in those days and the big meal was at noon. One thing we did for entertainment as a family was to 'go for a ride' to examine the local environment which exposed me to my surroundings, including what I would come to know as architecture. FARIBAULT 1921 to mid year 1935 In 1992 I paid a visit to Faribault before attending the Taliesin Fellowship reunion in Spring Green, Wisconsin. My purpose was part sentiment and part to look at the environment in which I grew up. What follows is primarily a picture tour. I will arrange the tour in roughly chronological order, but that is something of a guess. The Episcopal Church The Episcopal Church, Cathedral of Our Merciful Savior, was probably the first building that I recognized as being beautiful. Bishop Whipple, appointed to the Diocese of Minnesota in 1859, was the motivating force behind the creation of the church. The architect was James Renwick, Jr. Construction was started in 1869, around the same time as St. Patrick's Cathedral on 5th Avenue in New York City by the same architect. The later bell tower was designed by McKim, Mead & White and completed in 1902. On whole, the church is a beautiful, flawless piece of architecture. Across the street from the church building, the Bishop's residence was a two story Gothic Revival wood building with the main floor raised a short story above grade. A beautiful building I suspect was also designed by Renwick, it was demolished in 1934.

A Couple of Favorite Houses There was a house on upper 4th Avenue SW in an area known as Southern Heights that must be one of oldest and best vernacular houses in Fairbault. This was always one of my favorite pieces of architecture. The photographs are self explanatory. I don't know if the entrance vestibule is original or not, but otherwise the house remains essentially unchanged from the 1920's when I first saw it. It is a real jewel and we have to be grateful to the owners who have respected the integrity of the design. This house epitomizes what I call vernacular architecture. It is a direct expression of the needs of the inhabitants expressed in the simplest most direct way, with no semblance of pretense, and was built with locally available materials and labor.

On the other side of the street and a couple of blocks away is another gem built in 1868 in the Italianate style, the main body of the house remains intact and the addition to the left was designed with sensitivity to the original. On the lower right of the house and around the corner was an entrance to a small basement area that served as a grocery store in the twenties for the neighborhood, selling milk, bread, butter, and a few staples. In 1927 we lived just down the street and I remember going there to buy milk.

On Central Avenue, The Batchelder Block Central Avenue was the main commercial street and was developed primarily from 1885-1895 in the typical 2 and 3-story brick Italianate or Victorian buildings of overwrought, but at least interesting, design. The George F. Batchelder Block was built 20 years earlier in 1868. This is a lovely stone masonry 3-story building with the upper stories being carried at the street level by 4 stone arches. There is a stair to the upper floors on the right that opens to the street and could have presented an architectural problem, but not here. The architect took the direct approach. He formed the first arch on the right with the necessary width to accommodate the stair entrance, which makes for a very curious, narrow, compressed arch. He then divided the remaining space into three arches of equal spans. The arches are not symmetrical with the windows above and that is OK. A pragmatic, vernacular solution to a problem, it unexpectedly works beautifully. This is a lovely building. The rubble masonry at the top of the façade indicates that the elevation was at one time capped by a cornice. The storefront is particularly beautiful.

The Buckham Memorial Library At the south end of Central Avenue at 11 Division Street East is the Buckham Memorial Library. Built in 1929/30, the library was funded by Anna Buckham as a memorial to her late husband, Judge Thomas Scott Buckham. The architect was Charles Buckham, a nephew of Judge Buckham and a well known Vermont architect. The outcome was a wonderful building, my first exposure to what might be called contemporary architecture, and I loved it. Here was no icon of modernism like the Bauhaus of 1925/26, but still in a town of 16,000 mid-westerners, it was a monument to beauty and an important addition to the local culture. With walls built of Kasota limestone, the window and French door sashes were bronze and glazed with leaded glass in pale multi-hued shades of lavender that cut the glare from the sun. There was an adult reading room on one side of the entrance and a child's reading room on the other, with a two story high social room one level up from the entrance level at the back of the building that opened with French doors to a block long lawn. The place was lovely; I was impressed. I also took serious note of the casement windows. We had recently moved to a house with a barn, with a chicken coup that had two double hung windows. At the tender age of eight I decided that casement windows had to replace the double hung windows, so I removed the double hung sash and procured some lumber to make casement windows. My only tool was a jack knife so I didn't get very far, but the intent was there. That is what is important.

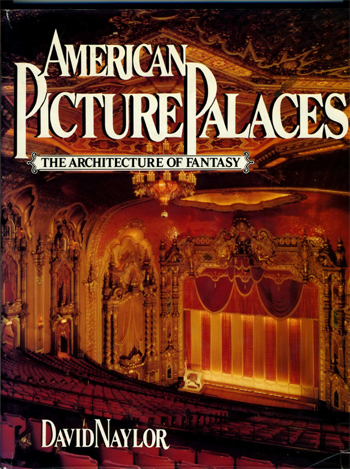

A Local Movie House Back on Central Avenue between 3rd and 4th Streets NW is the local movie house that was built in the 30's on the site of an earlier building destroyed by fire. The theater was in the mode of the day as an Eberson atmospheric design. The auditorium was styled after a Spanish courtyard topped with an arched blue sky ceiling sprinkled with twinkling stars and shifting clouds projected in a predetermined pattern. I loved it. Illusion is what the movies are all about and the theater was the ultimate illusion. Theater magnate Marcus Lowe said, "We sell tickets to theaters, not movies." So be it. From that time on the theater/movie palace played an important role in my life. For information on the movie palaces and the Eberson atmospheric theaters see American Picture Palaces, the Architecture of Fantasy by David Naylor (Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1999 [See: Library]).

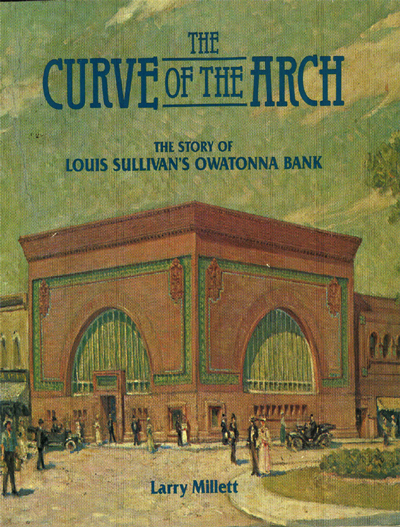

My mother had a friend a few miles away in Owatonna whom she visited occasionally in 1928 or 1929 with her brood. We always drove by the 1907 Sullivan bank. This was my first exposure to a contemporary major architectural masterpiece, and I like to think that I recognized it as such as a sub-teen. I still find it rather amazing that a small town banker would have the foresight and the fortitude to take on the task of employing a world class architect to design a small town bank. It says a lot about the intellectual climate of mid-America at the turn of the century, and maybe even today. This was the first of four or five other Sullivan banks in the upper Midwest. The Curve of The Arch, The Story of Louis Sullivan's Owatonna Bank, by Larry Millett (Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, 1985 [See: Library]) is an excellent book on the bank, its banker, and the good old middle-west horse sense that made the bank possible, and an immediate success with its patrons.

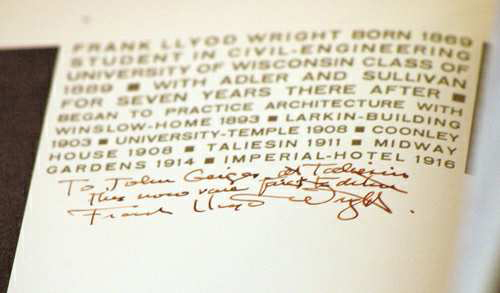

Minneapolis 1934 to 1943 When we moved to Minneapolis in midyear of 1934 my perception of architecture shifted from the vernacular to the ordinary. Not that my surroundings were bad, but that they were very ordinary 1900 clapboard houses with the front porch and everything that went with it. Our own house was an 1890 Queen Anne house of some merit, and I loved that house. My focus also shifted from the architectural drive-by to the Fine Arts Room of the Minneapolis Public Library, where my favorite book became a double folio volume of the work of the Adam brothers. On the visual scene the Minnesota Theater that became my focus. Here was a 1929 typical movie palace with a 4-story lobby modeled after the royal chapel at Versailles, complete with crystal chandeliers, real antiques with all the trimmings, including a gold leafed concert grand piano on the mezzanine. This was the Depression, and to be king for a day at the Minnesota was heaven. For 25 cents there was a double feature movie, an organ recital, and a vaudeville acts with the likes of Burns and Allen. You could stay for more than one show, which we sometimes did. The words of theater impresario Lowe bear repeating: "We sell tickets to theaters, not movies." Maybe Frank Lloyd Wright was saying the same thing within his own vocabulary. A University Education My four years at the University of Minnesota were not entirely wasted as some Wright enthusiasts would like to characterize any educational endeavor outside of the Taliesin Fellowship. I learned a great deal from a very few professors. However, everything changed on December 7, 1941. My two favorite professors entered the service at a very early date and I was left with critics for whom I had little respect. In my final semester, the summer of 1943, I took a course called Modeling for Architects taught by sculpture professor Burton. Because of the unsettling selective service process nothing was as usual, and only two of us signed up for this class. That didn't deter Professor Burton, but it did change the curriculum. We did nothing but talk for the entire semester, absolutely no laboratory work, only serious design philosophy talk. I credit that experience with my understanding of the relationship of space to solid form that still informs my understanding of the Wright paradigm to this day. An Army Air Force Education The next four years in the army didn't do a lot for my architectural education, but I did learn survival skills that stood me in good stead the Taliesin Fellowship. I was inducted as an aircraft maintenance engineer cadet. All my fellow students were aeronautical engineering students, so I had my work cut out for me to make the grade. Failure meant being reduced to being a foot soldier in the infantry. That was not a viable option. I received my commission as a Second Lieutenant on December 30, 1943 at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. I spent New Year's Eve at the bar of the now demolished Astor Hotel in New York City, and on January 2, 1944, I fulfilled a dream and bought a copy of the 1925 Wendingen for $125 from New York antiquarian bookseller William Helburn. This was my first major purchase of Frank Lloyd Wright published material. Mr. Wright autographed it to me in 1948 and I still have that much loved book.

Frank Lloyd Wright My first exposure to Frank Lloyd Wright was in an Introduction to Architecture course at the University of Minnesota in 1939. Images of contemporary buildings were being shown on the screen when the photograph of Fallingwater taken from below the falls suddenly appeared. I was thunderstruck. So began a love affair with the work of Frank Lloyd Wright that continues to this day. I went immediately to the architectural school library to see what this guy Wright was all about. They had, in a locked case to the right of the entrance door, a copy of the 1925 Wendingen, the 1931 Modern Architecture, being the Kahn Lectures (Princeton University Press), and maybe the 1932 Logmans Green publication of An Autobiography. I devoured everything I could find, but that was all there was in print about Wright at that time, except for periodicals. The library had bound copies of the Architectural Record containing Wright's contributions. I scoured the used book stores and found all 13 of the 1927/28 Architectural Records at twenty five cents each with the In the Nature of Materials articles. I still have them. I organized trips along with other U of M students to Spring Green, Chicago and Michigan sites to see the Wright work at those locations. After December 7, 1941, it seemed that if I were ever to see Taliesin West, now was the time to go. As students, we knew not what the immediate future might bring, so a group of us drove to Arizona to visit Taliesin West in December, 1941. Photos of Taliesin West as it appeared at that time, and other buildings that I photographed in my travels will figure in my future discussions of the Wright geometry.

Epilogue Before I begin my examination of the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, I would like to attempt to assess the influence that my pre-Wright architectural exposure had on my ready acceptance of the Wright philosophic approach to the subject. With my first viewing of Fallingwater, there was an instant understanding that this was a work of art. It is unlikely that this understanding could have occurred without some preconditioning. Wright's An Autobiography is replete with views about the ethics inherent in architecture as an art form. I liked Mrs. Coonley's assessment the best when she saw "the countenance of principle" in Wright's work, as recounted in An Autobiography (Duel Sloane and Pearce, 1943, p. 164). I think that I saw that same countenance of principle at work in what I characterize as the vernacular architecture of the Episcopal Church, the two houses and a commercial building in my home town of Faribault, Minnesota. The church is in the Gothic style, and one house and the commercial building are in what I call the Italianate style, but the vernacular triumphs over all. They remain essentially true to their vernacular roots. The 1902 McKim, Meade and White bell tower at the church is a bit of an intrusion and not very vernacular, but it is at least well done for what it is. The library is another story. Very much of its time, the building is slightly "Moderne," with hints of a variety of influences, including a bit of Mackintosh thrown in for good measure with the pilaster-like corners. All in all, it is a very good building -- the one that informed me about casement windows. The comparison of the Adam brothers work is not all that difficult to reconcile. Wright's early Oak Park work is very classical in its conception and there is strong similarity in concept, if not in style, between a classic Adams interior and a Wright interior where the walls, floor and ceiling are all architecturally managed. The similarity stops with the interior elevations, however. The Eberson atmospheric and movie palace Minnesota Theater are harder to reconcile with the Wright work. There is no question that I was fascinated with both, but I am not sure what that had to do with my interest in the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright. If I were intrigued with both there must be a common denominator somewhere, at least from my own very personal perspective. Most certainly, it revolves around the sense of drama inherent with the theater. Buying a ticket to the Minnesota Theater was buying into a world of make-believe and surroundings of opulence, even if it was all fantasy. Buying into the Taliesin Fellowship was entering into a world of ritual and drama of its own making, as well as into a world of great architecture and collected art. Mr. Wright said to Steve Oyakawa and me one day, "Every building has to have mystery." I think that somewhere within mystery and drama is where the connection with the theater lies. But there are just musings, and I will not attempt to carry this inquiry beyond my capabilities. Is it pure coincidence that most of the architectural work which attracted me as a child in Faribault was built in the same decade into which Mr. Wright was born? Probably not; Mr. Wright as a child must have been seeing similar local architecture in real time to what I was seeing as history. There was, in the intellectual and cultural climate of the upper Midwest, an awareness of and a desire for excellence in architecture. Picking James Renwick as architect for the Episcopal Church in 1868, the choice of Louis Sullivan as the architect for the National Farmer's Bank in Owatonna in 1907, and the selection of Charles Buckham, a nephew of Judge Thomas Scott Buckham and well known Vermont architect, to be the architect for the Buckham Library in 1928 (a span of 60 years) was no accident, but rather a part of a pattern of the previously mentioned intellectual and cultural climate. This was all part of what I see as good old mid-western horse sense. There was no intellectual artifice in these selections. These same 60 years afforded Frank Lloyd Wright his extended Oak Park period. |