|

To a greater or lesser

degree depending on the building, why is a Wright building beautiful? That beauty is rooted

in the spatial quality of the building, and the space is a

function of the geometry of the planes that determine the basic

character of the structure. Strong geometry appears first in the

floor plans of the earliest work but spatial quality appears,

along with geometry, a bit later in the Playroom of 1893 and the

Oak Park Studio of 1895, personal spaces for Wright. I make a

distinction between spaces that Wright created for himself,

‘personal spaces’, and those he created for clients. He lavished

his greatest talent on his own personal environments. He lived

in these spaces and molded them to his will until they required

no further refinement. I have discussed these particular spaces

earlier.

I admit that I came to my basic conclusions quite

inadvertently. While reading an essay about the influence of

Froebel on the manner in which Wright used geometry, in this

case with the Ross cottage, I found myself thinking, “This is

sheer nonsense. Wright simply did not think that way.” This

raised two obvious questions. The first is, if he didn’t think

“that” way, how did he think, and secondly, how did I know how

Wright thought? I had been exposed to Wright’s work for some

fifty years at this point and obviously drawn some

conclusions as to how he proceeded to solve architectural

problems. That didn’t mean I approached the problem solving

process by intellectual examination, but

nevertheless I had

concluded, at least in very broad terms, how he approached the

architectural design problem. The next step was to examine how

he thought, or did not think, about the Ross cottage.

The earliest published drawings of the Ross cottage were

drawn especially for Frank Lloyd Wright's

Ausgefurte Bauten; the Hitchcock

drawings are derivatives of these drawings. They are all right

for their intended purpose but are not adequate for serious

examination. Neither the preliminary nor working drawings have

ever been published, so a visit to the Getty Research Library

was in order to examine images of the original drawings. Before I get to

the Ross cottage, however, there are precursors to be

considered bridging the gap between Wright’s 1889 house for

himself and the 1902 Ross Cottage. After all, this is a period

of 13 years. A sea change had taken place in Wright’s design

vocabulary. The Ross cottage of 1902 is not only fascinating for

its geometry, but is also prototypical of almost all the

relevant forms common to Wright's residential work from 1902 to

the time of his death in 1959.

THE ROSS COTTAGE

PRECURSORS

By 1902, Wright was a major force in the field of

architecture with several masterpieces to his credit, including

the 1893 playroom added to his 1889 home, the 1895 Studio, the

1896 Romeo and Juliet windmill, the 1900 Bradley and Hickock

houses, and in 1902 the Heurtley and Willits houses, the

Hillside Home School buildings, and the Ross cottage.

The Ross and other concurrent cottages are of particular

importance for their simplicity and originality of concept. They

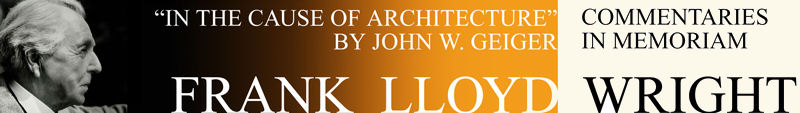

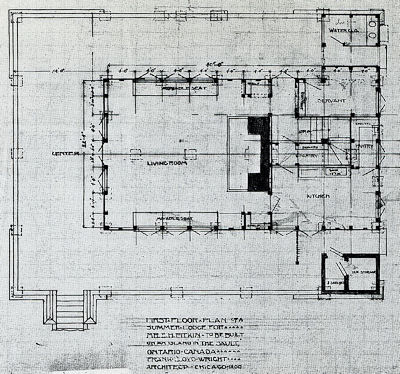

tend to be simple direct solutions to a problem. By 1900, he

reached a new plateau of maturity with the Pitkin cottage. Like

Wright’s own 1889 house, the Pitkin project is no masterpiece,

but the design is important for the ideas that it represents.

The most obvious feature of the scheme is the broad rectangular

stylobate that serves as a base for the entire structure. The

device is similar to the verandas in Wright’s 1889 house, but

here is used much more decisively. The main body of the house

is a simple rectangle that occupies the center portion of the

stylobate and is congruent with it at the back wall. There is an

8’-0” wide cross rectangle defined by two service areas

at the outside corners of the stylobate at the back. These

alignments create a cross gable at the first floor whose ridge

is in-line with the back wall of the second floor. The effect

produces a consciously designed relationship that approaches the

cruciform: what this cottage is all about. This

device is obvious on the elevations, as well as on the floor

plan, if you look. The broad chimney mass, which

becomes dominant in future

work, appears here for the first time and requires a walk

through on the second floor, but does emerge as an exterior

design element. Also, the first real, but incomplete, unit

system makes an appearance. The Swiss Chalet

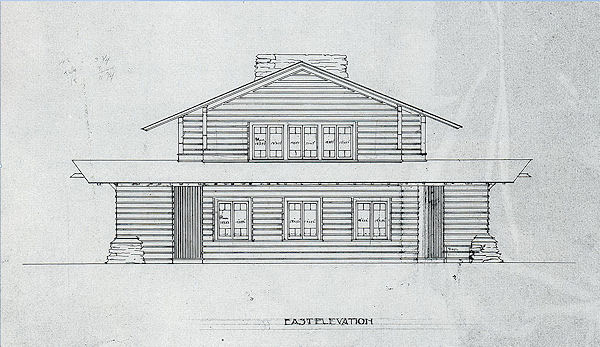

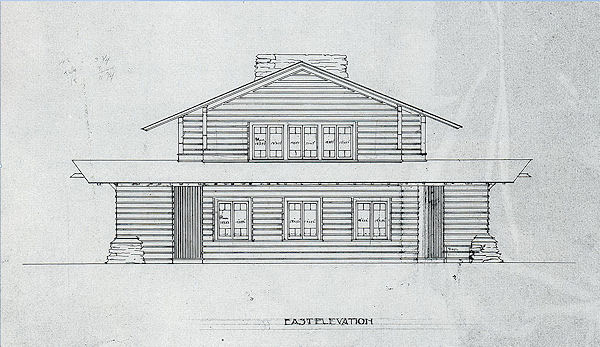

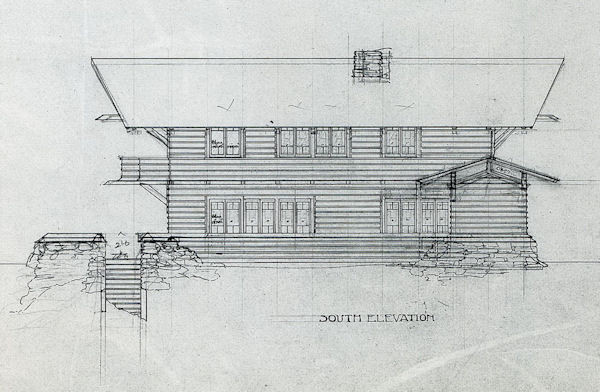

look is out of place in the context of the ideas demonstrated in

the concept of the job, which is clearly Wright’s. That look is

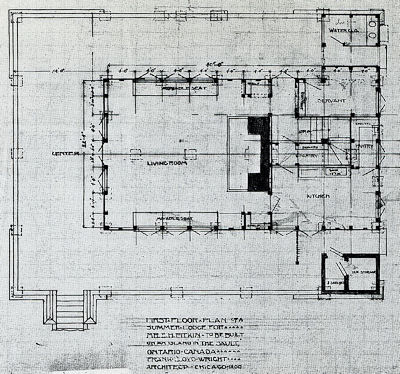

particularly offensive on the South Elevation. The East

Elevation best reveals Wright had in mind.

|

| Figure 1. Pitkin Cottage First Floor

Plan. Frank Lloyd Wright Archives, Drawing #0005.001 © Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Used by permission. |

| |

|

Figure 2. Pitkin Cottage East Elevation. Frank Lloyd

Wright Archives, Drawing 0005.009

© Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Used by permission. |

| |

|

Figure 3. Pitkin Cottage South Elevation. Frank Lloyd

Wright Archives, Drawing 0005.007

© Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Used by permission. |

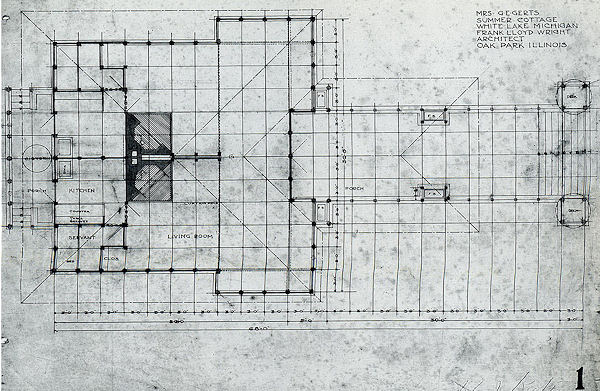

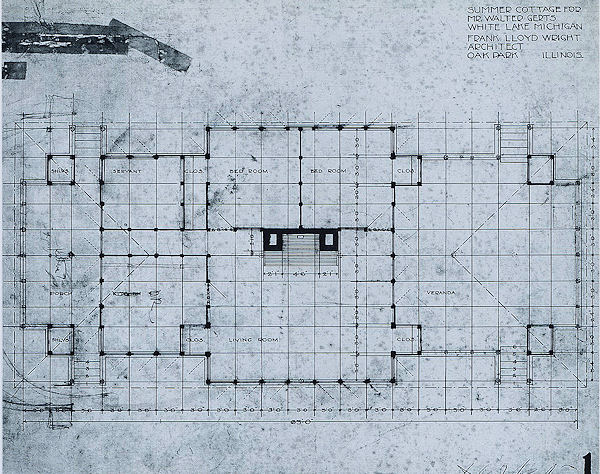

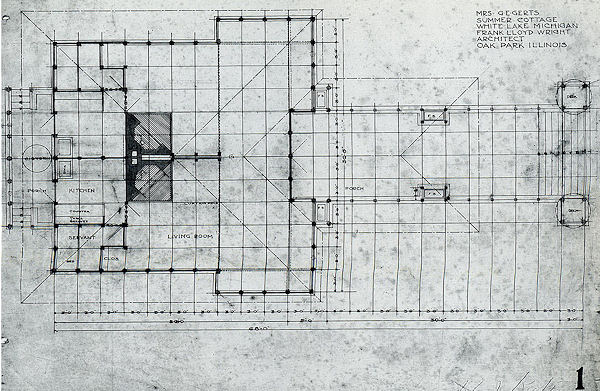

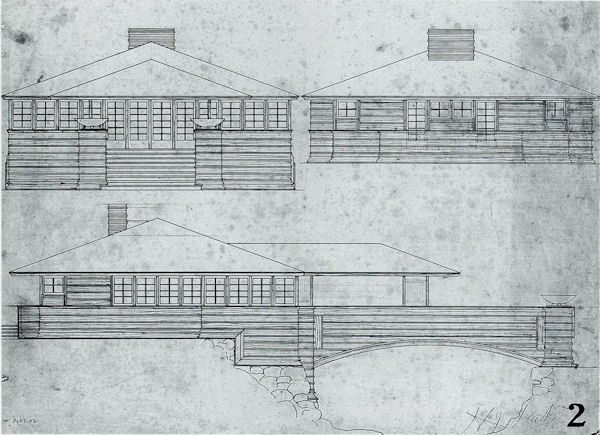

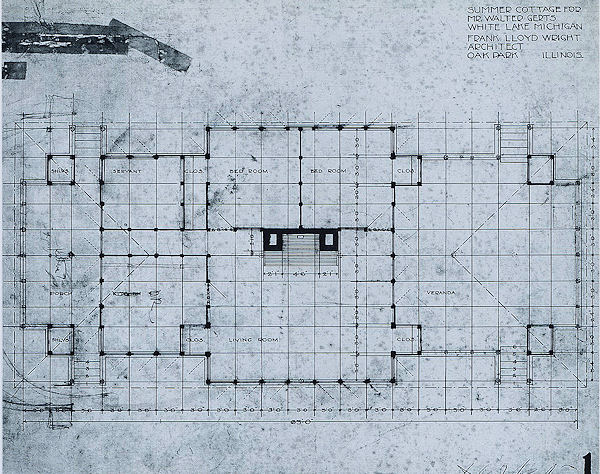

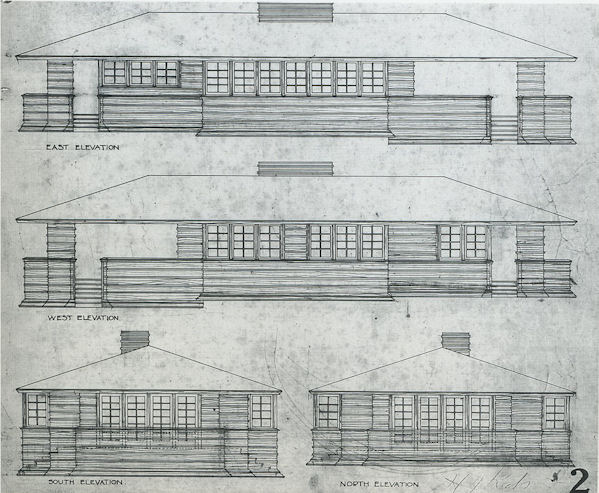

The George and Walter Gertscottages (Figures

4 and 5, and Figures 6 and 7, respectively) are

important for their clarity and elegance of concept. There is

nothing unaccounted for in these designs. Each is contained

under one big roof, a device that will become a hallmark of

Wright’s future work. The unit system is fully developed here,

except that he throws an occasional odd unit in each case to

accommodate a smaller dimension for the “pier” in the George

Gerts cottage. The pier makes a decisive appearance here for the

first time. The pier is essentially a masonry form and this

presence in a board and batten structure is somewhat

problematic, but the arrangement works architecturally to

provide visual structural support where needed.

|

Figure 4. George Gerts Cottage Floor Plan. Frank

Lloyd Wright Archives, Drawing #0202.001.

© Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Used by permission. |

| |

|

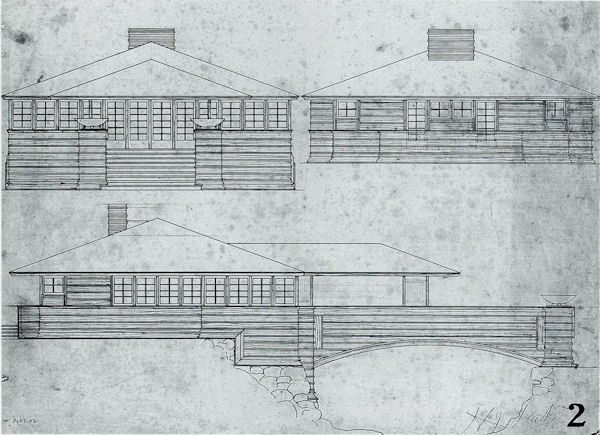

| Figure 5. George Gerts Cottage Elevations, Frank

Lloyd Wright Archives, Drawing #0202.002. © Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Used by permission. |

| |

|

Figure 6. Walter Gerts Cottage Floor Plan. Frank

Lloyd Wright Archives, Drawing #0203.001.

© Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Used by permission. |

| |

|

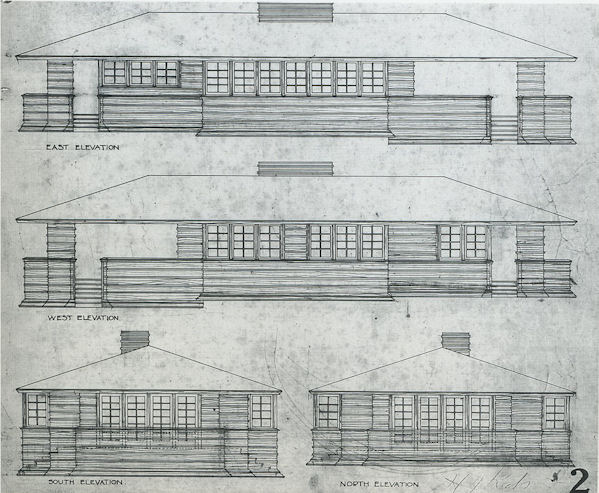

Figure 7. Walter Gerts Cottage Elevations. Frank

Lloyd Wright Archives, Drawing #0203.001

© Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Used by permission. |

THE ROSS COTTAGE

|

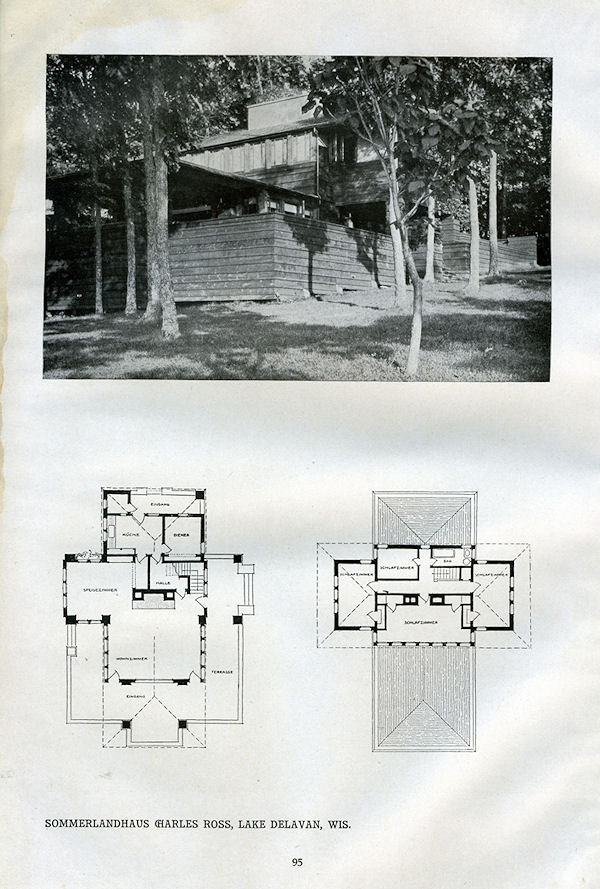

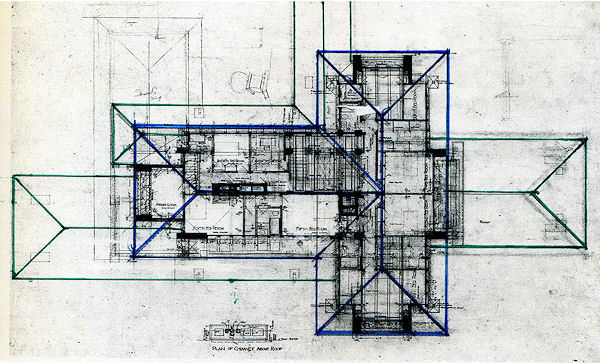

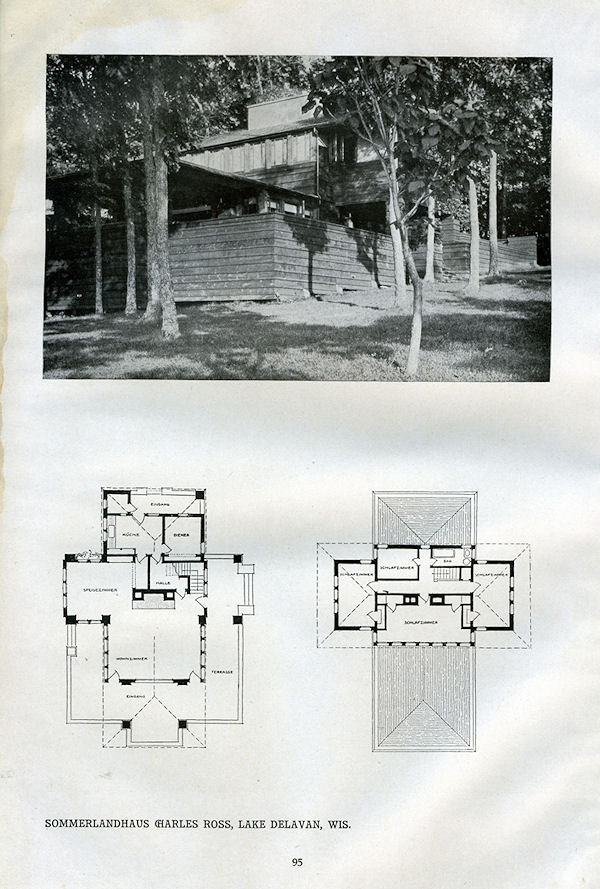

| Figure 8. Floor Plans and Photograph. Frank

Lloyd Wright, Ausgefuhrte Bauten |

The Ross cottage is the last of the structures that has a

pronounced stylobate, which here is the primary element of the

design. This work is simply amazing for clarity of

concept. Wright contemplates an entirely new architectural

grammar that he senses only in big overall terms. Any new

concept has to start this way. An idea must be worked

until the light bulb goes off and understanding occurs. We have

all experienced this; possibly in algebra class, or maybe

English Literature. Wright was not fully aware of what he

had done in this case, and that doesn’t really matter; the

essential grammar was evident.

The original drawings are in a somewhat distressed state, but

I would like to use them here anyway since they have never

before been published and they do provide a lot of information.

|

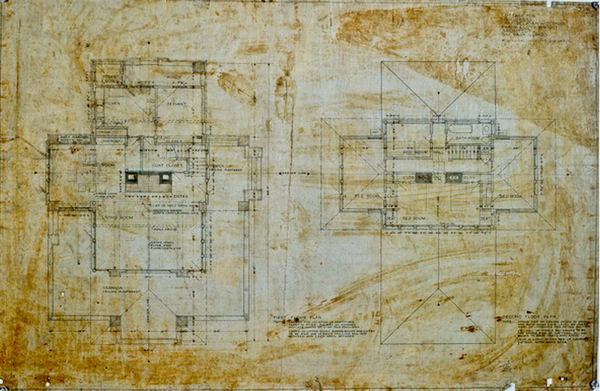

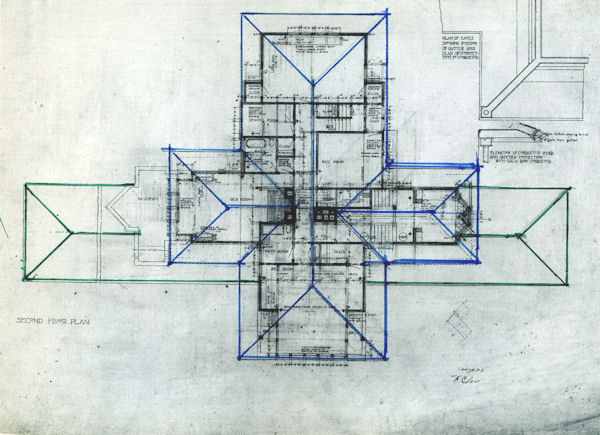

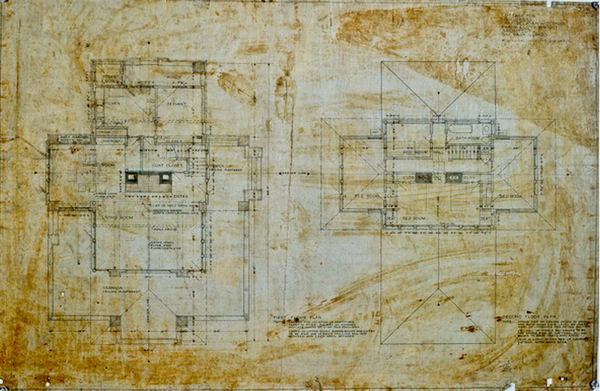

Figure 9. First and Second Floor Plans Frank

Lloyd Wright Archives, Drawing #0206.002.

© Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Used by permission. |

| |

|

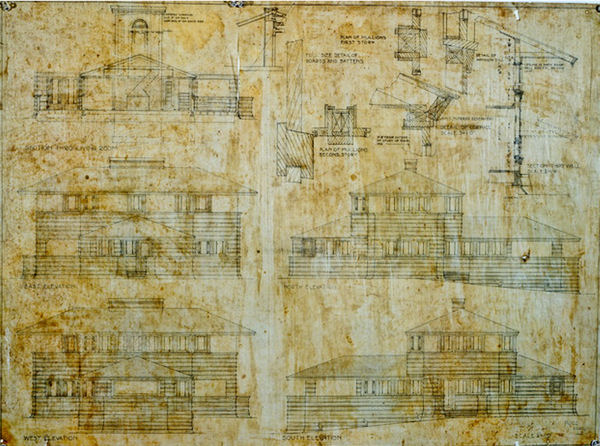

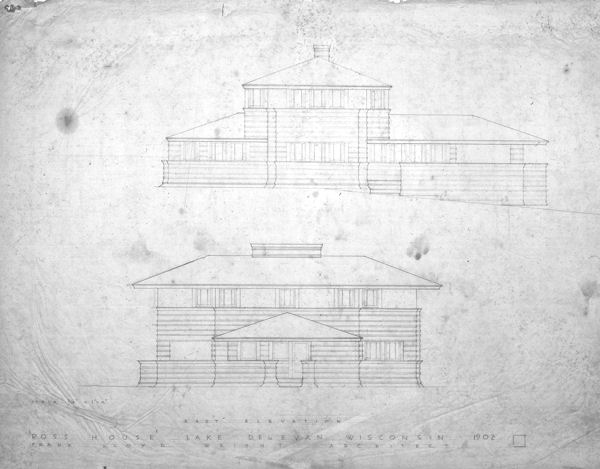

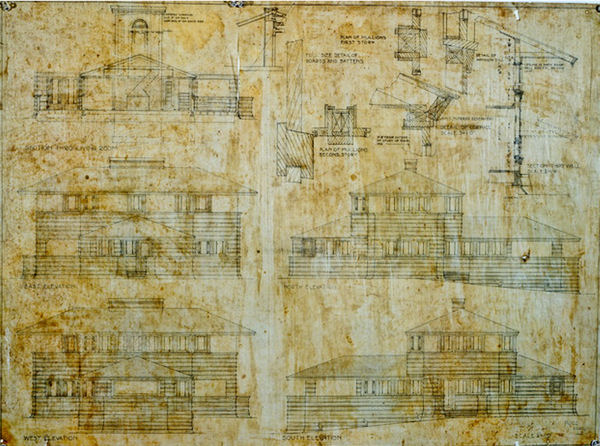

Figure 10. Elevations and Details. Frank Lloyd

Wright Archives, Drawing #0206.001.

© Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Used by permission. |

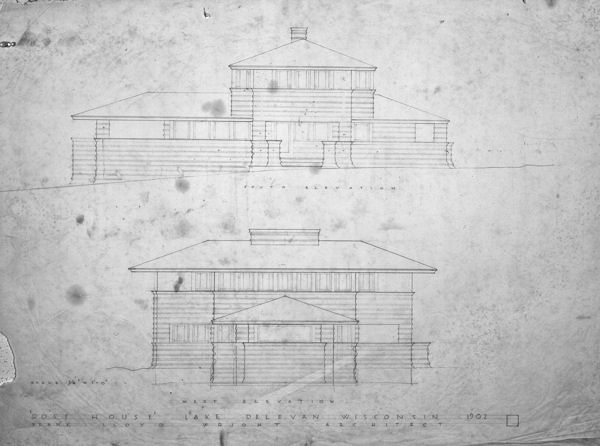

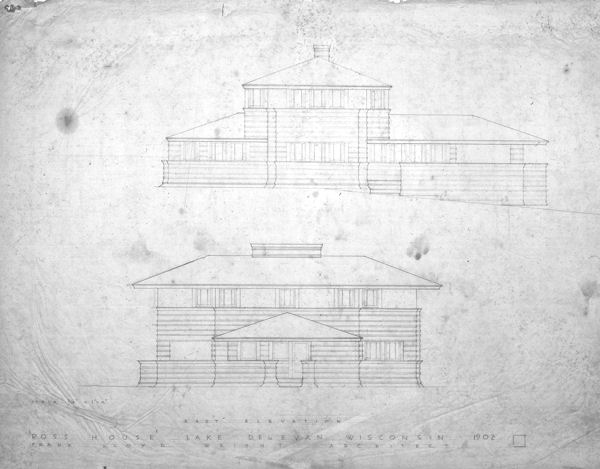

There are also two additional elevation sheets

that were obviously drawn much later:

|

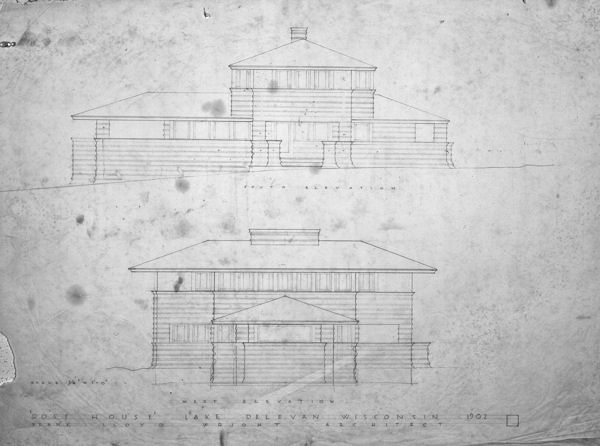

| Figure 11. Elevations. Frank Lloyd Wright Archives,

Drawing #0206.003. © Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Used by permission.

|

| |

|

| Figure 12. Elevations. Frank Lloyd Wright

Archives, Drawing #0206.004. © Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Used by permission. |

The house consists of three basic elements: the

stylobate or base on which the house rests, the lower hip roof,

and the upper hip roof turned 90 degrees to the lower. This

disposition of two equal width hip roof lines at a right angle

to each other is the hallmark of Wright's work for years

to come and emerges as a major factor in their beauty. The

geometry of the plan is as exact as any classical temple. The base

is thirteen units square and defined by the six major

piers. The lower hip roof, seven units wide and nineteen units

deep, centers on the stylobate, overhanging by one unit on

the front and extending beyond the stylobate five units on the

back. The upper hip roof is also seven units wide and overhangs

the stylobate on three sides by one unit, so that the

diagonals of the hips coincide with the diagonals of the square

stylobate base. The seven, one quarter unit square, visually

supporting piers have their diagonals on the diagonal of a hip.

The smaller columns determining the exterior closure line of the

living room are in line with the two larger columns at the front

and have one corner on the diagonal of the base. The chimney has

one face on the ridge line of the upper roof and is centered on

the ridge line of the lower roof. All this is very

geometrically regular but not dull or static

(Figure 13).

|

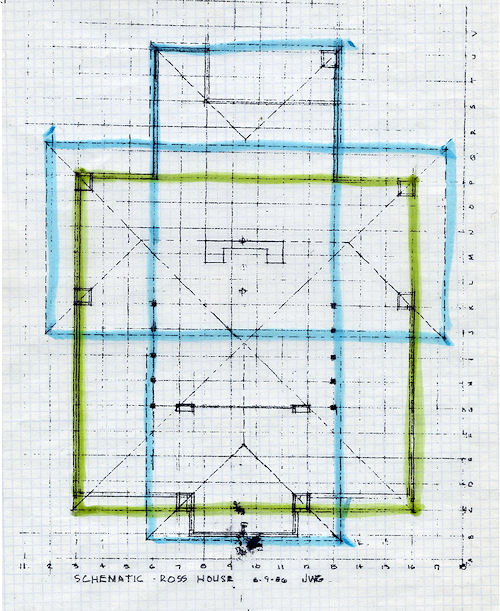

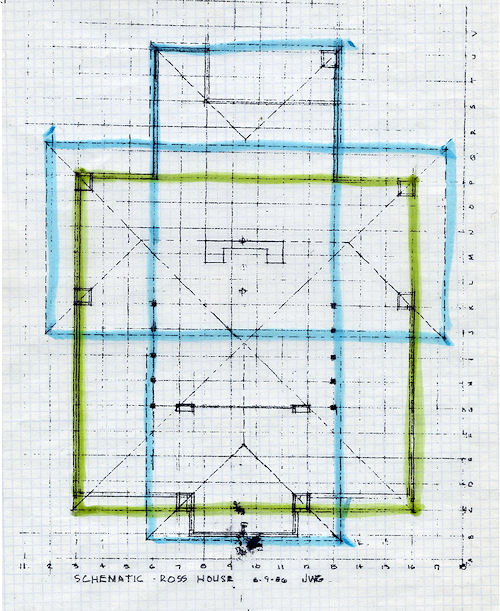

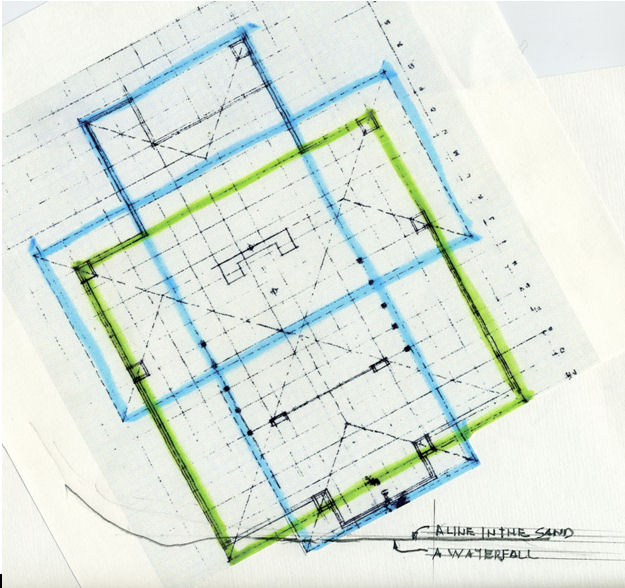

| Figure 13. Ross House Schematic Plan. John W. Geiger |

I have chosen to use this plan (drawn August

9, 1986) because it is dated and because it is enhanced by the

imprint of a beloved feline friend. I used green to outline

the stylobate because it is the closest to earth and blue for

the two roof outlines because they are closest to the sky. I

find the geometry demonstrated here to be absolutely fascinating

for the implications in his future work. As you have probably

noticed, I have drawn the stylobate as defined by the six square

piers because that is what was uppermost in Wright’s mind. The

front railing varies from the basic scheme and was a

mistake. Wright trys to do two different things here and

the combination doesn’t work.

The stylobate and the lower roof and upper roofs should

be considered as parallel horizontal planes. Separated by a

story height, they float freely in space, with the additional

plane of the earth being considered as the primary plane to

which the other planes are related. If you come in one unit line

from the roof perimeter and drop a vertical plane, you have the

space available for use as enclosed space. This form can

be considered for a one or two story space as required. Where more

space is needed, either for practical of aesthetic requirements,

the enclosing vertical plane can be moved out to the roof edge,

but no further. The plane can also be moved inward from

the one unit line for similar reasons, as in the living room.

The position of the two roofs can also be reversed,

as in

the two story living room of the Isabel Roberts house.

A space is generated between the plane of the first floor

roof and the stylobate. The stylobate continues outside the

confines of the lower roof to form a relationship with

the next available plane, which is the sky, wherever that happens

to be. The second floor roof not only creates a relationship

with the two constructed planes below, but where overhanging the

stylobate conversely establishes a relationship with the next

available plane below, which is the earth. Wright

renders a relationship with both earth and sky.

However, there is one big problem the way in which Wright

develops this scheme: the relationship of the front line of the

stylobate parapet to the roof above. He moves the parapet off

the unit line to the inside face of the wood pier and introduces

a projecting stylobate between these piers. This device

makes the piers appear to be free standing. The other

four piers defining the stylobate are in line with the parapet.

The front parapet should also be in line with the front

piers and on the unit line. He is trying to do two

different things with this front parapet where he should be

doing only one. He has already a schematic relationship

between the stylobate and the roof plane above

through simply

overhanging the stylobate by one unit. What he is trying to do

with the center projection is the reverse of what he has already

achieved; namely to project the stylobate with its attendant parapet

one unit beyond the roof line. He does this in a mature way with

the Robie house west terrace in 1908. This is 1902,

though, and

Wright is struggling to invent an entirely new way of looking at

architecture as a series of related planes. He pretty much does

that schematically with the Ross cottage, but a full realization

of what he had done had not yet entered into his conscious

thinking. That is understandable, considering the scope of his

undertaking.

With Robie he includes the balcony off the living and dining

rooms, and the staircase from the terrace down to the first

floor is in the equation. The two configurations of the

Ross schematic and the Robie west terrace are really the same

thing; one being the reverse of the other.

|

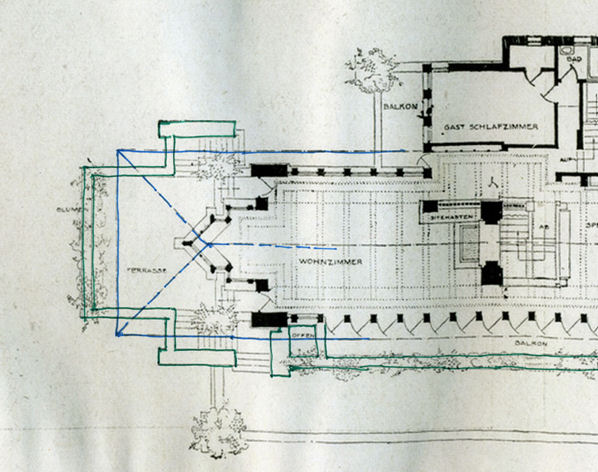

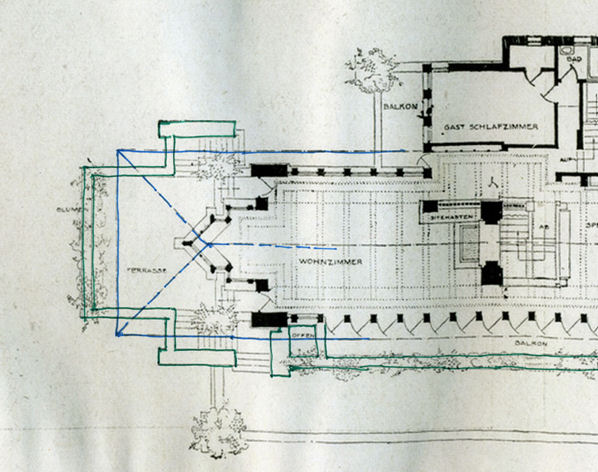

| Figure 14. Robie House Main Floor Plan, with colored

overlay by John Geiger. Sourced from Ausgefuhrte Bauten

Frank Lloyd Wright, p. 113. |

I am calling this simple relationship the Wright Paradigm, or

the WParadigm for short. This basic relationship will occurs

again and again in different guises in all of the best work for

the rest of his career. I see the relationship as basically

between two, or more, horizontal planes, but the vertical plane

of the balcony or terrace parapet also plays a secondary role as

a vertical plane forming a horizontal to vertical relationship

as well.

I also think that once Wright became aware of the WParadigm,

he saw it as a very simple key to produce quality in his work

and continued to keep the secret of how he worked from everyone,

including the staff. Maybe he didn't really see this approach

as a secret, but simply as his way of working. Possibly it just

never occurred to him that he might share the technique with

anyone else. He lived in a world of his own creation that was

not well populated with friends or enemies; or a wife and

children, for that matter. His one big need in life was to be

architecturally creative, and the second was for female

companionship.

The stylobate of the Ross cottage was to make its last

appearance for years to come, but the cruciform roof pattern is

the configuration that will have the greatest impact on the work

for the next five or six years. The form dominates all the best

work. The WParadigm will come later. The Walser, Barton and

deRhodes houses of 1903, 1903, and 1906, respectively, are

direct developments of the Ross cottage. The 1902 Willits house

and the 1904 Martin residence are both extremely sophisticated

examples of the cruciform roof pattern. Like Wright’s 1889 for

himself, the main roof dominates the composition. In both

of these houses Wright takes great care to keep all the major

architectural features of the house under outline of the

roof. There is no indication of the WParadigm. In the Willits

house, Wright extends the living room as a terrace at the front

of the house but takes care that the second floor roof has a

tight eave with the front elevation. There is no overhang of the

terrace by the roof, thus avoiding the WParadigm. Still, the

roof pattern is the dominant design consideration. The floor

plan had to fit the roof plan.

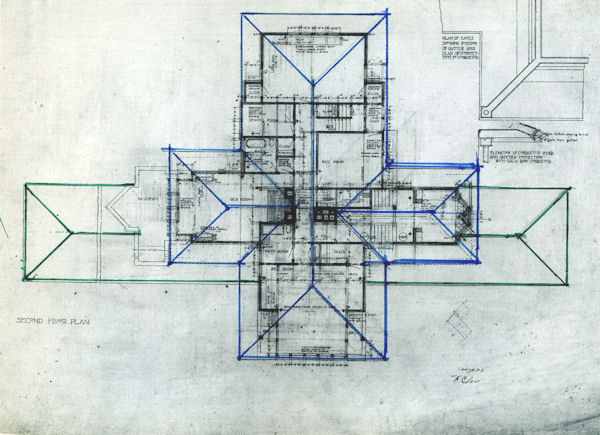

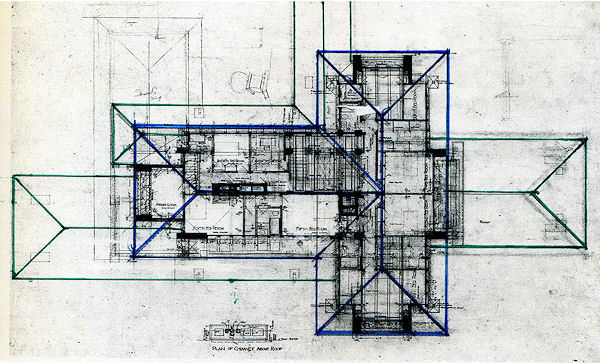

The roof plans of the Willits and

Martin houses that follow

clearly demonstrates the existence, and the importance of, the

roof as a geometric pattern, and the subservience of the floor

plan to that geometry.

|

| Figure 15. Willits house roof plan, with colored

overlay by John Geiger. Frank Lloyd Wright Archives,

Drawing #0208.004. © Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Used by permission. |

| |

|

|

Figure 16. Martin house roof plan, with colored overlay by

John Geiger. Frank Lloyd Wright Archives, Drawing

#0405.005. © Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Used by permission.. |

The WParadigm of the Robie house might not seem like a

sea change from the Willits and Martin houses, but it is, and as

such marks the end of the Oak Park Grammar as well as Wright’s

Oak Park life. Here is the beginning of the establishment of a

relationship between the floor plane and the roof plane that

would pervade Wright’s work for the rest of his life. The Oak

Park grammar had run full course and change was in the offing.

A GIANT LEAP FORWARD

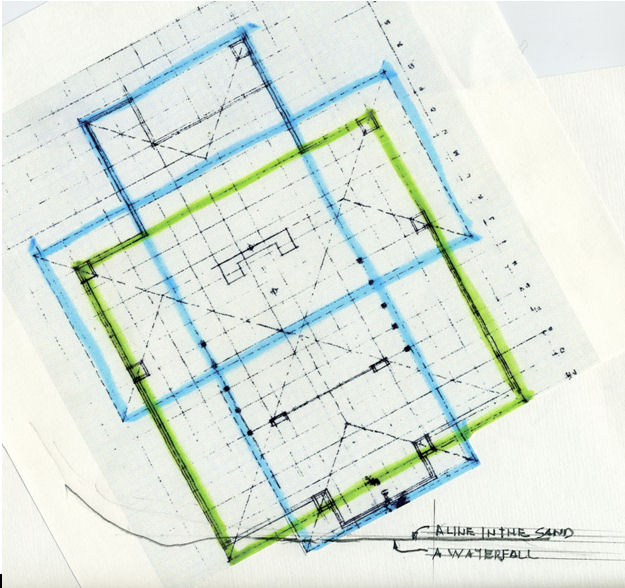

To start the giant leap forward, let us draw an

imaginary line in the sand. Take the Ross cottage schematic and

project the corners of the stylobate and the first floor roof

over the line in the sand. Then rechristen that line in the sand

a waterfall.

|

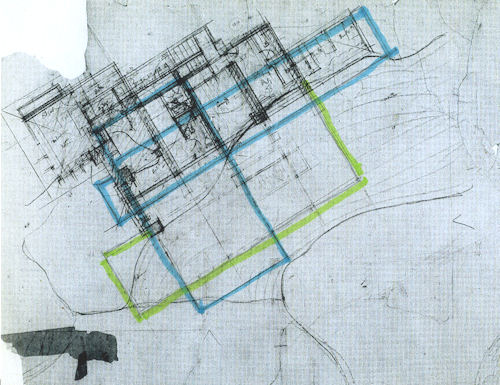

| Figure 17. The Ross schematic, revised. John

W. Geiger |

And what do you have?

You have Fallingwater.

|

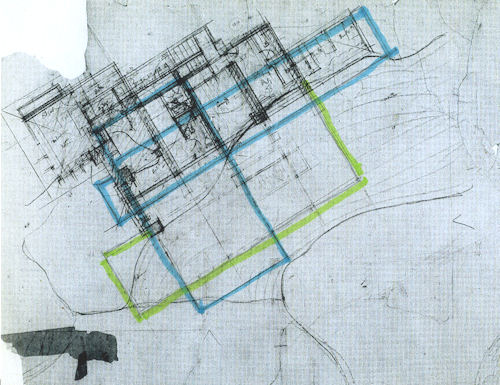

| Figure 18. Fallingwater, Original Sketch by Wright,

with color overlay by John Geiger. Frank Lloyd Wright

Archives, Drawing #3509.166.

© Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Used by permission. |

| |

|

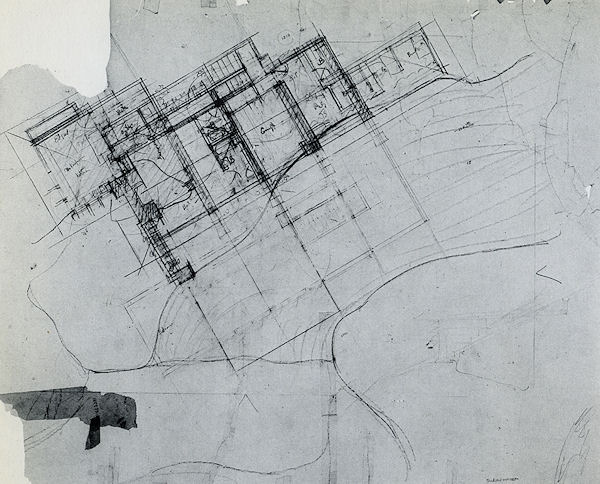

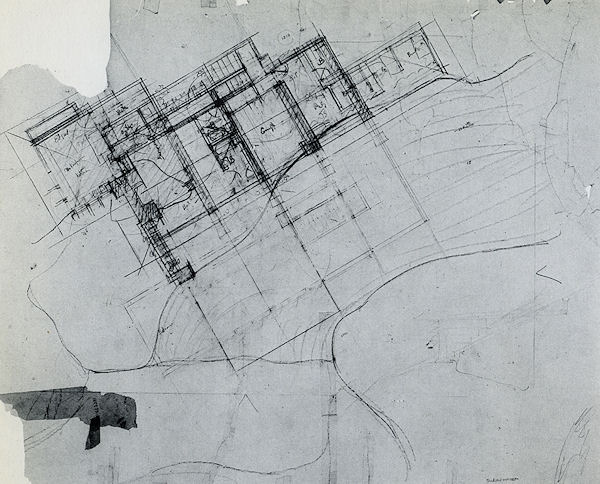

| Figure 19. Fallingwater, Original Sketch by Wright.

Frank Lloyd Wright Archives, Drawing #3602.166. © Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Used by permission. |

I have repeated the drawing without my intrusion

so that you can see that I only enhanced lines already

drawn by Wright.

What makes Fallingwater “work” is the overlap of the two

constructed planes of the first and second floors with the two

natural planes of the top and the bottom of the waterfall; hence

the engagement of the fall of the water from one plane to the

other; or Fallingwater.

The rest is history.

|

|