Introduction

EPISODE GUIDE

EPISODE 1

EPISODE 2

- MY LAST SUMMER AT THE FELLOWSHIP AND THE LOS ANGELES 60 YEARS OF LIVING ARCHITECTURE PAVILION

- THE ROSS COTTAGE AND A THESIS

- IN WRIGHT'S HAND

EPISODE 3

OTHER ESSAYS

- WHAT KIND OF A MAN WAS MR. WRIGHT TO WORK FOR?

- THE MERRY WIVES OF TALIESIN, A FEW HUSBANDS, PLUS SOME MERRY MEN

- A SUMMER'S WORK -- NOT IN THE TALIESIN DRAFTING ROOM: THE NEILS HOUSE

"IN THE CAUSE OF ARCHITECTURE":

COMMENTARIES IN MEMORIAM

the taliesin fellowship 2

my last summer at the fellowship

and the

Los Angeles

60 Years of Living Architecture Pavilion

Having relegated my first summer at the Fellowship to history, I now do the same for my last summer with that venerable "institution." Frank Lloyd Wright used to say, by way of Sullivan, “Take care of the terminals and the rest will take care of itself.” Taking care of the book ends of my tenure at the Fellowship is not to say that there is nothing to be said about the “in between” years, because there are yet volumes to be written on that subject, but not here and now.

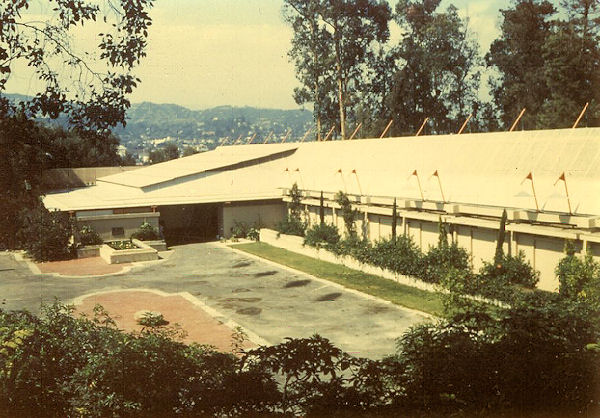

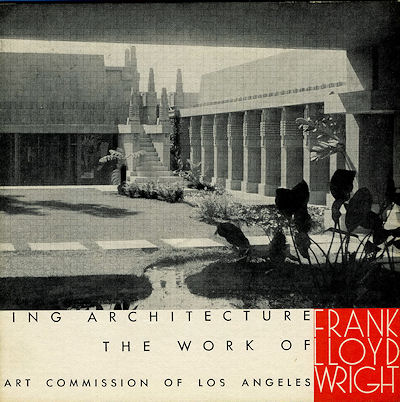

The spring and summer of 1954 were spent in Los Angeles supervision the construction of a pavilion at Hollyhock House that would house the last showing of Mr. Wright’s 60 Years of Living Architecture exhibition. Before the Los Angeles adventure, back in the fall of 1953, I joined a number of other apprentices who were working on the construction of the pavilion and Usonian house at the 60 Years of Living Architecture exhibition at the site of the future Guggenheim Museum in New York City. After the opening ceremony on November 23, 1953, Mr. Wright left me in New York as his representative at the exhibition.

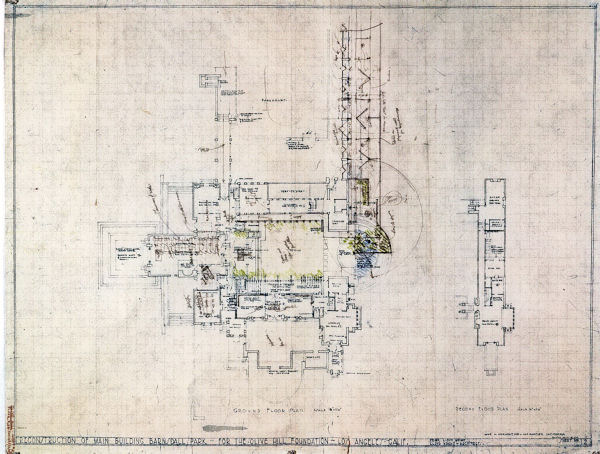

| The exhibition closed after about 4 weeks but months passed before the installation was finally dismantled and shipped to Los Angeles. I followed the show to the West Coast and was the supervising apprentice for the construction of a pavilion at Hollyhock House that housed the exhibition in Los Angeles. Ken Ross of the Los Angeles Cultural Affairs Department negotiated with Mr. Wright for the Los Angeles showing, and Mr. Wright designed a pavilion to house the exhibition that was to become an integral, albeit temporary, part of Hollyhock House. Preparations for the construction of that building were well under way when I arrived. Ross had already secured the pro bono services Morris S. Pynoos as the general contractor and Eugene Birnbaum as the structural engineer. Both men were highly qualified and the show would not have gone on without their selfless contributions. What follows is a narrative of how I handled this assignment. I don’t know how other apprentices handled their supervision jobs, but I do know how I handled this one. Hollyhock House already had a rich history of trials and tribulations, and was now to be enriched by a gallery from the hand of Frank Lloyd Wright. The house proper was connected to the garage by a 216’ long series of “dog kennels.” I doubt that there were ever any canines housed in these constructions but they did make a impressive connection of the house to the garage. The kennels were flanked on the west side by a 132’ long entrance court serving the house plus a 72’ long car court serving three garages. These are pretty impressive dimensions for a private residence and very much in scale with the development of a pavilion to house the 60 Years show. Wright added a 20’ wide pavilion the full length of the kennels on the east, and a “Lecture Room” on the west encompassing the entire car court, which was about 40’x 72’. The gallery extended beyond the kennels to the south and up a short flight of existing concrete stairs to cover a portion of the circular pool terminating the east/west axis of the house courtyard. One of the fascinating aspects of this development is Mr. Wright’s first sketch of the pavilion which is imposed on a drawing bearing the title of the Olive Hill Foundation and shows the conversion of the two bedrooms and baths between the library and the master suite into a Gallery. The drawing credits Frank Lloyd Wright and Lloyd Wright as architects. Lloyd Wright is generally given credit for this conversion and the finished product does bear his hallmark. The drawing is in the Frank Lloyd Wright Archives, so there is a question of who did what. There is ample evidence on the drawing in Mr. Wright’s hand to validate his participation. The Olive Hill Foundation was founded by Mrs. Murray in memory of her son who was killed in WWII. The foundation leased the house from the city and was in possession of the premises during the exhibition. We had access to the house gallery across a portion of the pool, through the courtyard and loggia, but no access to the house proper except a peek into the living room from the loggia.

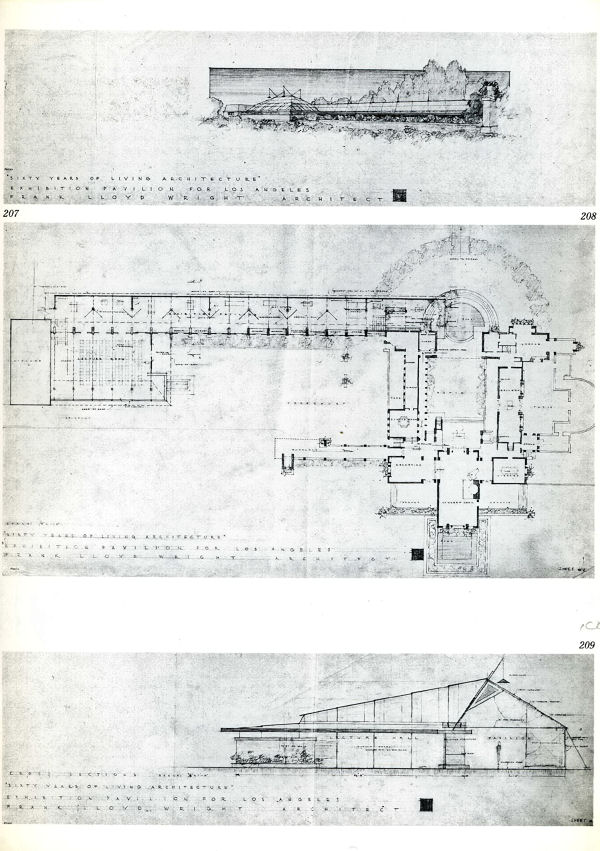

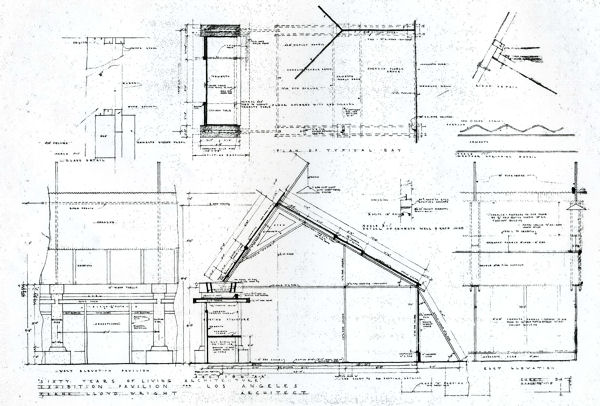

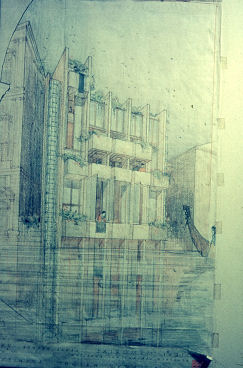

ORIGINAL PRESENTATION DRAWINGS

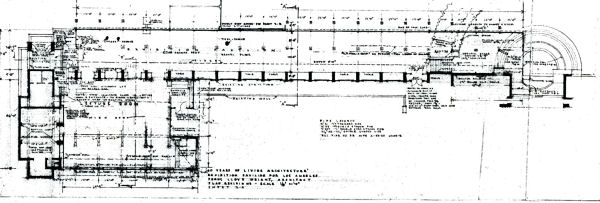

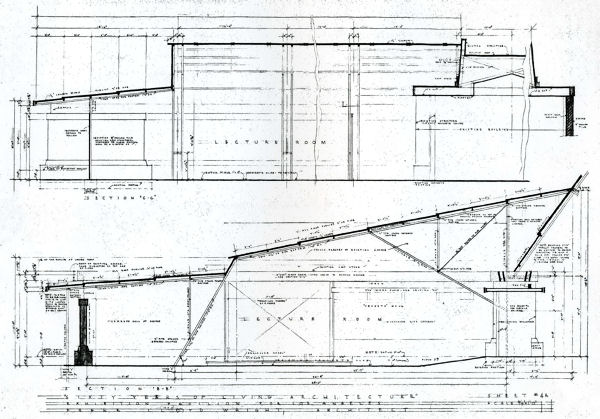

The preliminary drawings (Figure 2) are a development of Wright’s original sketch and are pretty accurate except for the garage, shown as a simple rectangle, which it was not. Jack Howe did all three drawings. While the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation was in possession of all the original drawings of Hollyhock House, they were in folders and not readily accessible for review by the drafting room personnel. Since there was no library of published books available to the drafting room, the apprentices probably had less information available to them about existing work than was available in a library at a public institution. Rather than make the effort to lookup information about the garage, which has never been published, I am sure Jack said to himself, “Let them work it out on the job,” and that is what happened. After the show opened Mr. Wright asked me to make a drawing enclosing the pavilion and lecture rooms with glass and to include the east terrace of the garage. I did make the drawing but knowing that Mr. Wright would probably not remember having asked me to do so, I don’t think I ever sent him a print. That drawing represents a status somewhere between an “as built” drawing and an “enclosure” drawing. The drawing (Figure 3) also shows the revised main entrance, which I will get to.

The original entrance to the house from the existing courtyard was almost ceremonial for a Wright house, but here the prominence of the gallery roof above the dog kennels tends to de-emphasize the house entrance, and leads an arriving visitor to the entrance of the new facility. Even here you are confronted by a recessed entrance instead of an obvious entrance door; a typical Wright non-processional approach.

The entrance to the pavilion was at the south side of the Lecture Hall following what had been the driveway to the car court and garages. The approach was straight on, as indicated on Figure 2. Wright would change this in the course of events, something we examine later. The Lecture Hall was an approximately 40' by 70' foot space with a very high ceiling with no natural light, except that which streamed in between the piers of the former dog kennels and beckoned toward a right turn into the space of the main exhibition hall. This delightful, brightly lighted space with a roof primarily of corrugated plastic was very narrow but long, 20' x 192' feet, together with another, higher 48' length at the far south end of the gallery. The approach to the upper area was a flight of existing concrete stairs that raised the visitor 4' up to the level of the main courtyard of the house and the circular pool with its landscaped hemicycle.

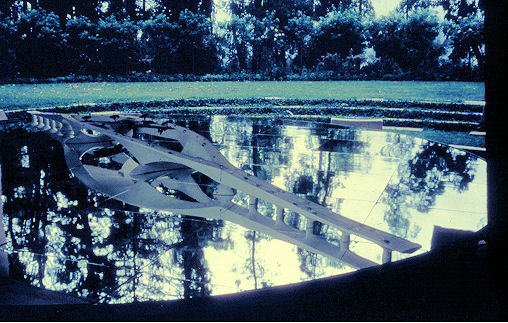

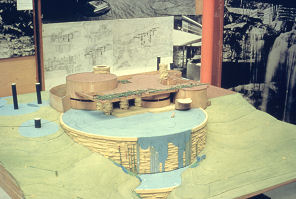

The roof of the main exhibition space extended part way over the pool providing a link to the courtyard of the house and was completely open to the elements at that end. A model of the San Francisco concrete bridge made by Wright’s associate Aaron Green in San Francisco was mounted on an eight foot round segmented mirror platform. Mr. Wright placed the model in the center of the circular pool just inches above the water; an ideal location for a bridge.

There was a tight turn around the corner of the pool into the courtyard. I recall that we provided a wider access with a wood platform and a railing of some kind to keep visors from falling into the pool, but I don’t presently have any archival evidence of the solution. At the far end of the courtyard vistors entered the house by way of the glazed doors of the loggia outside the living room.The only access within the house was the loggia and aforementioned gallery (accessed by two more left turns and a right turn) created in 1947 by Frank Lloyd Wright, with associated architect and son Lloyd Wright, from the two bedrooms and baths of the original house. This internal gallery was used to display the Broadacre City model. Visitors exited the exhibition by retracing their entrance route. The first problem to be resolved was a structural one. The exhibition building in New York had a structural frame built from pipe scaffolding. This innovative use of a structural support system is deserving of a separate investigation. Los Angeles is earthquake country and pipe scaffolding was out of the question. The supporting structure needed a welded steel frame. We had to make a new set of structural drawings on the job to get a building permit, and those drawings are identified with a letter after the sheet number. We accomplished this in Lloyd Wright’s studio with the help of Eric Wright and Joe Fabris, who was supervising the Anderton Court building in Beverly Hills. I still have those drawings. Time was of the essence if we were to get this building built in time for the scheduled exhibition opening. I did what was necessary the get the job done, and simply advised Mr. Wright as to what I was doing. There was no time to ask his approval. I remember in particular telling him by mail that we were going to paint the steel pipe bents coral and the purlins red. No response. When he saw the completed building for the first time there was no comment so I guess my decisions, including color, were okay. Pynoos built the entire building in 21 days. Pynoos, who was himself a structural engineer but functioning as a building contractor in this instance, had already started a dialog with structural engineer Birnbaum. Their solution to the structural problem was fairly simple, at least in the main exhibition space. In New York, the roof was supported by a series of columns, purlins and roof rafters. The rafters became a pair to support the roof loads. Besinger describes this episode in his chapter entitled "Summer 1953." In Los Angeles, we again used the pair of roof rafters, separated by a one foot pipe spreader, that became a part of a welded pipe "bent" at 12' on center to align with the piers of the dog kennels. The earthquake lateral loads were absorbed on the outside of the building with a pipe at 60 degrees to the horizontal to a dead man of concrete buried in the earth on the east side of the building. There was one intervening pipe column 8’-4” from the east wall and the west end support appears to just rest on the existing kennel piers. I do not remember how we made that connection; there does not appear to be any. One pipe size for all members was essential from Wright’s point of view and that is what we had. Since this was a temporary building we didn’t pay a lot of attention to making it weather tight, at least from the heating and ventilation perspective, in sunny southern California. The area between the roof of the kennels and the bottom of the new pipe bent was just left open to the weather but baffled by a couple of wood fascia members. That “opening” provided ventilation where there was no other provision for such an essential consideration in the exhibition area. The Lecture Hall, on the other hand, had no natural light or ventilation, but I don’t recall that being a problem at the time. After all, this was California where the weather seldom ever gets too hot or too cold and the structure was temporary as well as a Frank Lloyd Wright design. Wright often left some practical problems such as heating and ventilation to chance.

The structural problem at the Exhibition Hall was not so simple, because we had a 36' clear span to deal with. Sheet 4A (Figure 11) details how we dealt with that problem. The pair of high roof rafters turned down at 60 degrees to the horizontal at the floor to become inclined columns. This pair of columns and attendant trussed superstructure acted as a rigid frame to take the lateral loads as well as the vertical loads. The lower sloped roof was supported again by a pair of roof rafters at one end by the inclined columns, and at the other end by a pipe column placed outside the existing court yard wall so as not impose any loads on the existing structure. One detail I was particularly fond of was the device to reduce the stress of the lower roof rafters. We used a spreader between the paired rafters in both the lower roof and the pair of inclined columns, connecting them with a vertical pipe column. That reduced the span of the lower roof rafters by 20% and, incidentally, helped prevent visitors from tripping overt inclined pipe columns. It also provided triangulation with the inclined columns to help with lateral loads.

The cladding material for the building was, in retrospect, fascinating. The material for the roof and side walls was “Cemestos," manufactured by Johns-Manville. They donated the material for both the New York building and the one in Los Angeles. Cemestos consisted of a solid insulating core one-and one-quarter-inches thick, coated each side with a one-eighth inch thick coating of cement-asbestos. This was the in-fill material for the Carlson House, for example, and is no longer available for obvious reasons. The material was self supporting for a four-foot span, and since we were using a four-foot module that was okay. For the roof, we butted the panels and covered the joint with a batten; probably “Transite,” which was one-quarter inch thick panel of the cement-asbestos material used to coat the Cemestos panels. No roofing membrane was required. The Cemestos panels acted as their own water-shed. The application worked for a temporary building but exposure of the insulating core at the ends of the panel would not work for a permanent installation. Here it did and certainly solved the "roofing problem." The exhibition was shipped by rail from New York to Los Angeles and the models sustained some damage in transit. Mr. Wright told me, “John, you should have gone down to the freight yard and supervised the packing of the rail car. With that word of admonition, we will say no more.” That was his way of dealing with the situation. Once he had his say, the thought was banished from his head forever. We set up a repair shop in the Bekins warehouse in downtown Los Angeles. Former apprentice volunteers John and Martha Paul drove up from Long Beach every day, and together with George James, Ruth James, and Bob Clark set to work repairing the damage. There was some money available from the insurance and, as I recall, Eric Wright and Tom Casey were paid volunteers.

In the main exhibition hall I thought that the individual roofs of the dog kennels between the piers looked “dated” and needed some freshening. I suggested that we try a new continuous fascia. Pynoos said, “You won’t like it.” We tried it and I didn’t like it, so we just faced the existing fascia with a new redwood 1 x 8. When Mr. Wright arrived he had the same feeling as I did about the kennel fascia, except that he knew what to do about it. He nailed a redwood 1" x 4" with the bottom one inch below the existing fascia and running continuous the entire length of the kennels. That did the trick. The kennels immediately became part of the new construction. Now, that is genius.

He also painted the east face of the cast stone pier base red and continued the color as a floor stripe across the floor to the opposite wall. That is an old trick to slow down the eye and make the space look wider. Chaos reigned supreme in setting up of the exhibition. Oscar Stonorov, who had designed the original exhibition, was on hand to help set up the installation, but as you might expect Mr. Wright took over. The main exhibition space Mr. Wright set up looked great, but the panels not used in the main exhibition area were just placed randomly under the low roof of the Lecture Hall and made no sense what so ever. Mr. Wright couldn’t care less. Oscar left in a huff. Our volunteer crew was on hand to share in the chaos. Mr. Wright loved chaos. Mr. Wright arrived at the site about 3:00 PM the day before the opening and decided that the entrance to the building into the Lecture Hall should be moved. This change involved tearing out 24 feet of existing wall and replacing it with 36 feel of new wall, including the entrance doors, and pouring a new 12' x 12' foot concrete slab. Under other circumstances this might have been seen as an unreasonable request, but with Wright, such was just par for the course. Pynoos went to work. By 11:00 AM the next day the new walls were in place and the quick setting concrete slab had been poured (see Figure 2 and Figure 3 for the two entrances). That afternoon, the day of the opening, Mr. Wright arrived unexpectedly at about 3:00 PM already dressed in a black suit, cape and hat, all set for the opening. He walked straight across the newly poured concrete without comment about the moved entrance and made the left turn into the Lecture Hall. There he was confronted by a gaping garage door opening rather than the projection screen that he had been expecting to see. He was furious and started screaming and waving his cane at me. I knew that the slide show was important to Mr. Wright. I had given the foreman a drawing for the screen frame the first thing in the morning and told him that no matter what was going on at 5:00 PM he was to stop whatever he was doing and build the frame and screen and install it. Mr. Wright's anger was entirely without cause. I was also angry, but with good cause, and was in no mood to put up with his temper tantrum. I was never one to expect accolades from Mr. Wright but this was the first time I was the subject of his anger. I didn’t like it. I am not easily cowed and this situation was no different. I decided that if he didn’t get off his high horse and treat me with respect he wasn’t going to get his screen. I went to him after about 30 minutes and told him that screen was all ready to go and all he had to do was to give me the go ahead. He wouldn’t speak with me. I tried the same routine 30 minutes later with the same results. At 4:45 PM we were approaching the witching hour and I had to either get his approval, or go through with my threat. This time I did get a begrudging acknowledgement and I was off the hook. I don’t know to this day what I would have done if I had not received his acknowledgement. By 5:45 PM the screen was in place and Rita, the contractor’s wife, arrived with a station wagon full of folding chairs. The projector had been focused and the show was ready to roll. I went home, cleaned up, changed my clothes, and got myself back the site in time to open the door on the driver’s side when Mr. Wright’s limousine arrived. Mr. Wright's grand daughter stepped out and said, “Good evening, John,” in a voice that could belong only to Anne Baxter.

I didn’t realize until much later that the screen scenario was the final straw that broke the camel’s back and gave me cause to leave the Fellowship. This one incident would not have provoked that decision, but my uneasiness with what was going on at the Fellowship was a primary contributing factor. Besinger says in one of his letters to a friend while I was in New York that he didn’t think that I would ever return to the Fellowship. He was correct. When I left New York, I stopped at Taliesin and picked up all belongings, including my car, and took the things home to Minneapolis and the car and myself to California. If I had been contemplating leaving the Fellowship at this time I was not consciously aware of it. But I had been unhappy for some time with what I saw as Mrs. Wright’s scheme to seize control of the Fellowship from Mr. Wright in order to serve her own interests. My position was that if Mr. Wright could not regain control of the Fellowship from Mrs. Wright, my contribution “In the Cause of Architecture” was pointless. I did not want to stick around and bear witness to the decline and fall of the Wright Empire. The Los Angeles incident was a mere catalyst. When the Los Angeles exhibition was completed I had the show packed and sent it by rail to Spring Green. I took special care in packing all the original drawings in a separate boxes and made sure that all was clearly marked. I advised Mr. Wright of my actions, so that the materials could be easily retrieved once in Wisconsin. The rail car would probably sit on a siding for months. Before Mr. Wright returned to Wisconsin he asked me to make a drawing enclosing the pavilion in glass and to include the east porch of the garage in the scheme. That drawing, which I still possess, is published here for the first time (Figure 3). Speaking of original drawings, Mr. Wright hung the Masieri drawing on the wall at the stairs at the south end of the Exhibition Hall. The problem with this placement was that the new pavilion roof sloped back there against the wall of the house proper. Considering the nature of a temporary building, we had left this intersection open to the sky. It never rains in Los Angeles in the summer. Cold damp air, however, drifted down the wall during the night and by morning the drawing was rumpled and sagging from the exposure to the night air and humidity. By 10:00 AM the paper had dried out and looked none the worse for the wear. We didn’t place the value on a drawing at that time that we would today. After all, Jack could always make a new one. Lloyd Wright called me one night and complained about the state of Masieri. He was, of course, correct, so I moved it. There were 6 or 8 other original drawings of California projects added to the exhibition for this showing.

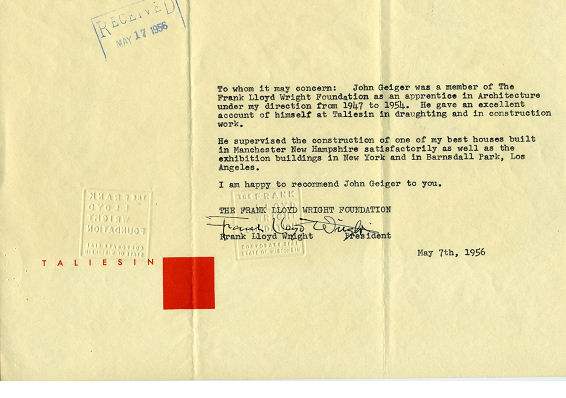

Another addition to the exhibition subsequent to its original content was what I called the “bible." When Oscar Stonorov was putting the show together he photoduplicated hundreds of drawings from which to make his final selections. These copies were bound into a twenty-inch square, four volume set, with redwood plywood covers. These found their place on a drafting table on the east side of the stone paved exhibition area. Mr. Wright sat there for hours redesigning almost everything from 1889 on. For the 60 Years exhibition in New York two copies made of the bible, bound in grey plastic, were made available to the public on a continuous table on the west side of the pavilion. In Los Angeles, they were available on built-in tables in each of the dog kennels. We provided stools so that the interested visitors could spend hours perusing these volumes if they so chose. While I was trying to get his attention about the slide screen, Mr. Wright was busy redesigning his own work. After this adventure, Mr. Wright assigned me to the Arch Oboler Continuation (stone box) projectas construction supervisor. Oboler and I were never destined to be soul mates and my involvement didn’t last very long. I returned to Minneapolis to remodel my mother’s Queen Anne house and simply wrote Mr. Wright a letter telling him that I was leaving the Fellowship. I was not going to go through the charade of fake goodbyes that would characterize a real life, in person, departure from the Fellowship. While I was in Minneapolis, Wes called me and asked me supervise construction of the Milwaukee Synagogue, as I recall it. That time frame is wrong but it had to do with that building. I explained that I was involved in a family architectural job and was not available, which sufficed as an answer. I have never regretted a day I spent at the Fellowship and never regretted the timing and manner in which I left the Fellowship. That phase of my life that had run its course and come to the finish, simple as that. It was just over. Two years later I wrote Mr. Wright requesting a letter of recommendation to the California State Board of Architectural Examiners and he responded with the following letter and cover letter:

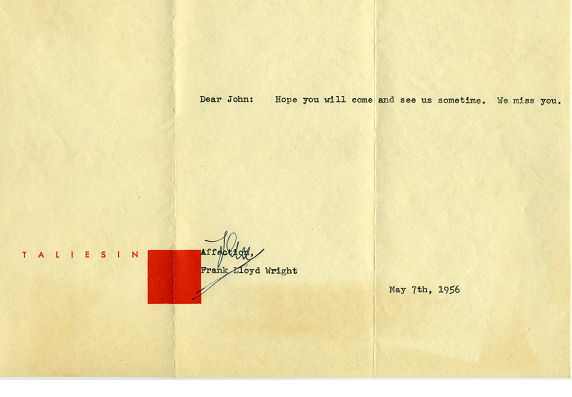

The “come and see us” was a nice gesture, but we both knew that I never would. The Fellowship was a glorious spiritual, intellectual and romantic adventure in the cause of architecture: a love affair in search of the truth, an affair of the spirit, but as we all know, there is nothing quite so final as a love affair that is over. The love endures; the affair is history.

|